Generations-based array

Intro

I was intrigued by the sparse map/set described in Russ Cox’s article.

And I’m not the only one: this exact implementation is used in Go source code more than once! The compiler uses it for many ID-like maps and sets; regexp package uses it for a queue.

But there is one thing that is still bugging me: it’s hard to make it very efficient. All operations I care about are O(1), but get and set operations clearly become slower in comparison with a straightforward slice approach.

In fact, if your arrays are not that big (less than 0xffff bytes?), you might be better off using a slice with O(n) clear operation. If you do many get+set, the increased overhead may be too much.

In this article, I’ll propose a different data structure that can replace a sparse-dense map (and set) if you don’t need the iteration over the elements.

This discussion is not Go-specific, but I’ll use Go in the examples.

The Problem

Let me start with a problem that we’re trying to address.

Imagine that you need a mapping structure that you can re-use. Something like a map[uint16]T, but with a more predictable allocations pattern.

Your function may look like this:

func doWork(s *state) result {

s.map.Reset() // You want the memory to be re-used

// Do the work using the map.

// Only get+set operations are used here.

}

If your “map” can re-use the memory properly, this code may become zero-alloc.

Our requirements can be described as follows:

| Operation | Complexity |

|---|---|

| Set | O(1) |

| Get | O(1) |

| Reset | O(1) |

We want it all, plus the efficient memory re-use.

We’ll analyze these choices today:

map[uint16]T[]TsparseMapgenMap

The slice and map solutions do not fit our requirements, but we’ll use them for a comparison.

Benchmark Results

Let’s start by comparing the raw performance.

| Data Structure | Set | Get | Reset |

|---|---|---|---|

| map | (x17.9) 47802 | (x28.6) 36922 | 1801 |

| slice | 2665 | 1289 | 6450 |

| sparse | (x6.7) 17859 | (x1.89) 2435 | 16 |

| generations | (x1.1) 3068 | (x1.04) 1349 | 26 |

Observations:

- Map is heavily outclassed

- Both sparse and generation maps have a crazy-fast reset

- Even with 5000 elements (8*5000=40000 bytes), a slice reset takes noticeable time

sparse.set()operation is ~7 times slower than slice!sparse.get()operation is ~2 times slower than slice- Generations map is almost as fast as a slice, but reset is much faster

The sparse and generations map do not zero their data during the reset operation. Therefore, avoid storing pointers in there. These pointers will be “held” by the container for a potentially long period of time, causing memory leaks. I would only recommend using both sparse and generations-based data structures with simple pointer-free.

You can find the exact benchmarks code here.

Some benchmark notes:

- I used a real-world sparse-dense implementation

- Every

get/setgoes through a noinline wrapper to avoid the unwanted optimizations - Every

get/settest runs the operation 5000 times - Every benchmark is using 5000 elements (it’s important for slice reset)

- The measurements above are divided by 10 for an easier interpretation

- The value type used is

int(8 bytes on my x86-64 machine)

Now, you should be cautious about random benchmarks posted on the internet. But no matter how you write and/or run these, generations map will always be faster than a sparse-dense map (or set). It’s almost as fast as a slice solution while still having a very fast O(1) reset.

There are reasons for it to be faster. Let’s talk about them.

Sparse Map Issues

Why sparse.set() operation is so slow?

When it comes to insertion of a new value, the sparse map has to do two memory writes. One for the sparse and one for the dense. Updating the existing value only writes to dense.

func (s *sparseMap[T]) Set(k int32, v T) {

i := s.sparse[k]

if i < int32(len(s.dense)) && s.dense[i].key == k {

s.dense[i].val = v

return

}

s.dense = append(s.dense, sparseEntry[T]{k, v})

s.sparse[k] = int32(len(s.dense)) - 1

}

Another issue is that two slices mean twice as much boundchecks that can occur. And while you can be careful and use uint keys and check for the bounds yourself to stop compiler from generating an implicit boundcheck, you’ll still pay for these if statements.

The sparse.get() operation also suffers from a double memory read.

Generations Map

It’s possible to use some of the ideas behind the sparse-dense map and create an even more specialized data structure.

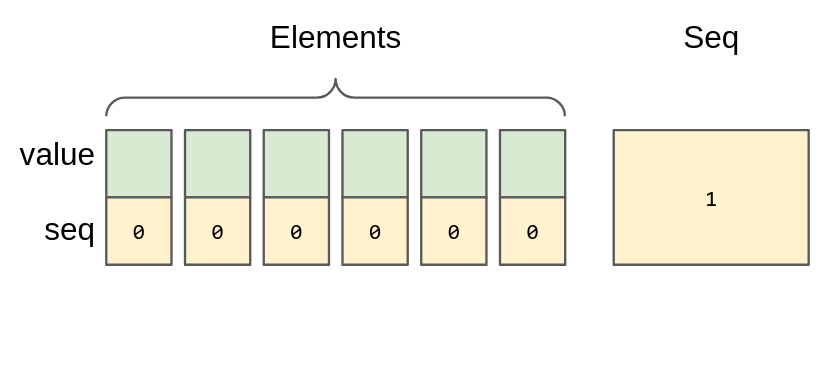

type genMapElem[T any] struct {

seq uint32

val T

}

type genMap[T any] struct {

elems []genMapElem[T]

seq uint32

}

func newGenMap[T any](n int) *genMap[T] {

return &genMap[T]{

elems: make([]genMapElem[T], n),

seq: 1,

}

}

Every element will have a generation counter (seq). The container itself will have its own counter. The container’s counter starts with 1, while elements start with 0.

Both get and set operations look very similar to the slice version, but with a seq check.

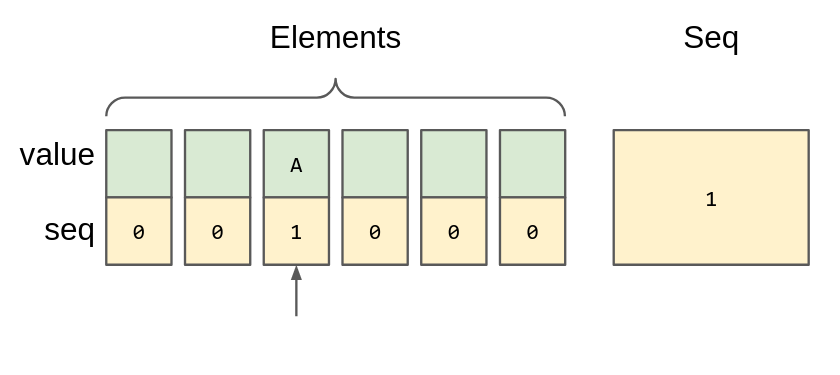

func (m *genMap[T]) Set(k uint, v T) {

if k < uint(len(m.elems)) {

m.elems[k] = genMapElem[T]{val: v, seq: m.seq}

}

}

Setting the element means updating the element’s counter to the container’s counter along with the value.

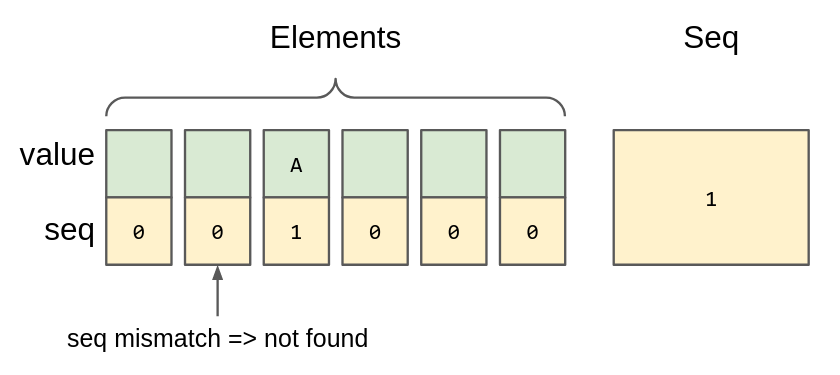

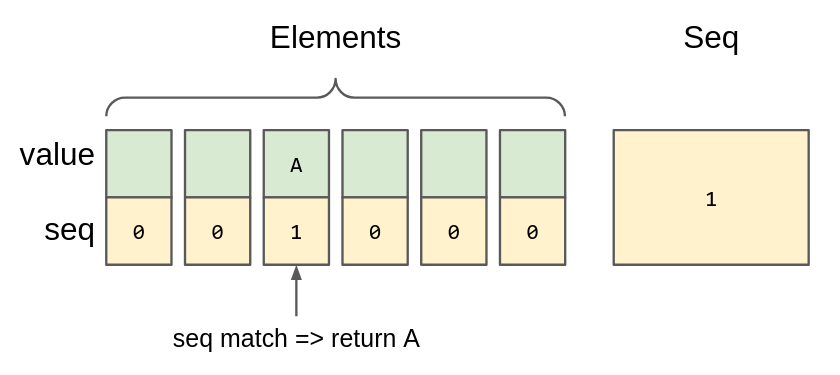

func (m *genMap[T]) Get(k uint) T {

if k < uint(len(m.elems)) {

el := m.elems[k]

if el.seq == m.seq {

return el.val

}

}

var zero T

return zero

}

If seq of the element is identical to the container’s counter, then this element is defined. Otherwise, it doesn’t matter what are the contents of this element.

|

|

You can probably already guess how Reset will look like:

func (m *genMap[T]) Reset() {

m.seq++

}

Well, this is good enough for the most use cases, but there is a small chance that our uint32 will overflow, making some undefined elements defined. Increasing the seq size to uint64 could help, but it will increase the per-element size overhead. Instead, we can do a real clear operation once in MaxUint32 resets.

func (m *genMap[T]) Reset() {

if m.seq == math.MaxUint32 {

m.seq = 1

clear(m.elems)

} else {

m.seq++

}

}

It’s definitely possible to use uint8 or uint16 for the seq field. That would mean less per-element size overhead at the price of a more frequent data clear.

- The generations map does exactly 1 memory read and write

- It’s easier to get rid of all implicit boundchecks

- Its memory consumption is comparable to the sparse-dense array

- The

Resetcomplexity is constant (amortized) - Arguably, it’s even easier to implement and understand than a sparse-dense map

It’s possible to make a generations-based set too. The get operation can be turned into contains with ease. With sets, only the counters are needed.

func (m *genSet) Contains(k uint) bool {

if k < uint(len(m.counters)) {

return m.counters[k] == m.seq

}

return false

}

It may sound fascinating, right? Well, you can’t use this data structure as a drop-in replacement for a sparse-dense. For instance, a generations-based map can’t be iterated efficiently.

You can add a length counter if you really need it, but that will add some extra overhead to the set operation. I would advise you not to do so. The main reason this structure can be so fast is its simplicity.

The average memory usage will be higher, since a referenced sparse-dense implementation doesn’t allocate n elements for the dense right away; it only allocates the entire sparse storage. So, if you only ever populate the array up to n/2, the approximate size usage would be 1.5n instead of a worst-case 2n scenario. The generations-based array would require the entire slice to be allocated right away, leading to a 2n memory usage scenario.

Conclusion

I used this data structure in my pathfinding library for Go. The results were great: 5-8% speedup just for a simple data structure change. Keep in mind that this library is already heavily optimized, so every couple of percentages count.

In turn, this pathfinding library was used in a game I released on Steam: Roboden.

Therefore, I would consider this data structure to be production-ready.